Your Vertebral Discs and Back Pain

Sherwin Nicholson | Updated May 4, 2020

Disc Health

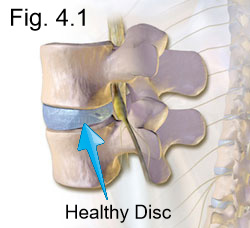

Figure 4.1 illustrates a section of a healthy spine that is properly aligned. The muscle groups that support it should be kept balanced to ideally maintain optimal disc pressure. Here, there is an even distribution of force directed towards all sides.

When lifting an object or bending, the distribution of force on the disc should be kept even. Your hips and knees must be positioned to provide the flexibility needed to maintain a stable posture during the exertion.

Specific muscle groups of the back, hip and legs are required to both contract or lengthen to do this safely. Appropriate and effective lower back exercises help to maintain the balance needed for protection.

Disc Problems and Factors

Although many factors can cause vertebral and disc problems, a number of problems can stem from not maintaining a neutral posture.

Without neutral posture, you’ll have chronic imbalances that not only can lead to injury, but to your vertebrae also.

Your spine is quite flexible and tolerant, so for most of the time, it’s easy to keep a neutral posture (or near neutral) to prevent any injury.

However, if you are already suffering, it’s likely that you’ll have some range of wear and tear on your vertebrae. If you were to go to a physiotherapist, they would also likely reveal a number of muscle imbalances.

Prevention is key because any underlying problems that are not resolved, will make you very prone to accelerated wear, bulging, rupture or herniation.

If you are familiar with the term, “slipped disc”, you’ll be surprised to know that they do not ‘slip’. It is a common misunderstanding. They do however bulge, shrink or herniate (tear, rupture).

The most common time when you can injure your back is when you’re not using the right technique to lift and move an object. Poor lifting technique is responsible for many injuries. Over time, we usually develop very poor habits that can accelerate this wear.

Disc Bulge and Herniation

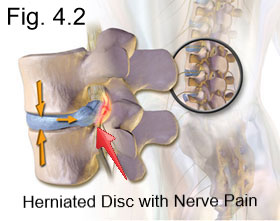

Figure 4.2, Shows a rupture (or herniation). This rupture occurs when the tough outer layer of cartilage has weakened from excessive pressure or aging and has caused the softer, inner layer of cartilage to protrude through. The weakening creates a bulge that exits through an area of low resistance such as near the nerve root.

Bulges are a common situation and are painful especially when the bulge creates excessive pressure on the nerve.

Disc Rupture

It can also hurt if the  rupture has released its contents from within to the surrounding tissues.

rupture has released its contents from within to the surrounding tissues.

These contents contain very potent inflammatory proteins and markers that are meant to initiate the immune response to repair.

However, they are also known for generating inflammatory signals and pain through an attempted repair initiation process.

In some cases, people can have no symptoms of pain whatsoever but still have damage.

Disc Thinning

When the contents are released, this very tough cushion dries out and becomes thinner. With time, it can heal but may remain thinner as it is very difficult for it to re-hydrate after herniating.

Naturally, for any healthy disc, there is some loss of water which will re-hydrate with rest and time. This is why you are slightly taller in the morning after a nights sleep as compared to your decreased height at bedtime. The added height is sometimes lost however withing the first 2 hours upon standing.

Bulging or herniation will naturally heal over a period of weeks to months without any treatment other than rest. However, if underlying causes that place excessive wear and demand on your spine are not addressed, then a cycle of injury and temporary healing and relief will inevitably reoccur.

This will result in progressive aging and degeneration of the disc, where it loses is natural hydration, becomes thinner, and much less flexible as  a result. It may also remain unable to reabsorb the herniated area, resulting in a bulge that places constant pressure on nearby nerve roots.

a result. It may also remain unable to reabsorb the herniated area, resulting in a bulge that places constant pressure on nearby nerve roots.

Figure 4.3 illustrates the progression of degeneration in the spine. A healthy disc is depicted at the top.

When there is a bulge, the strong outer layer of cartilage known as the Annulus Fibrosis remains intact, but the inner material known as the Nucleus Pulposus puts pressure thereby producing a bulge.

Depending on the severity of the bulge, there will be different pain signals that you will feel downstream from nerve compression. This can range from a mild tingling in the area just outside the spine, to sciatica, to full numbness.

If the Annulus Fibrosis tears (annular tear) the inner contents exits through creating a more focused injury. This material then pushes out onto a nerve.

Chronic Lumbar Issues

Chronic bulging, tearing and rupturing, along with healing as mentioned above may eventually lead to thinning as repair gradually becomes poorer and less effective.

Because the disc is now thinner, your spinal flexibility becomes progressively reduced. It is the optimal and maximal height that allows for the greatest flexibility for your spine.

The vertebrae on either side of the thinned disc are now physically closer. When these bones of closer and you then bend, the edges of the vertebrae become more likely to touch. When they do come in contact, there is wear to the bone. This damage triggers additional irritation and inflammatory repair.

The immune system tries to repair this area with a method of bone tissue repair. This can appear on an X-ray or MRI as osteophyte formation.

A repair can become so progressed that it irritates the surrounding tissues and nerves, causing pain. This formation can build and limit your flexibility.

For some, their degeneration has become so severe, that the vertebrae develop enough repair formation to fuse themselves together to stabilize and control the joint.

The lowest disc (and also the most prone), known as the L5-S1 in figure 4.3, has reached this point. Here, the person has endured so much discomfort that surgery may be considered to permanently fuse the vertebrae to restrict further movement to control the pain.

These discs are especially prone to injury if you work very long hours at your desk and already have symptoms.

Learn about the routine causes of your pain

The Facet Joint

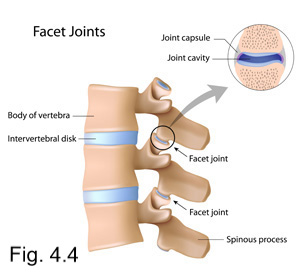

There are special joints that are part of each vertebrae of your spine, called facet joints. They connect, align and protect each vertebra and disc involved.

The joint capsules in between provide lubrication and flexibility . It gives the articulated flexibility needed to distribute pressure evenly along the spine and to keep the vertebrae aligned.

. It gives the articulated flexibility needed to distribute pressure evenly along the spine and to keep the vertebrae aligned.

When the discs in between become too thin as in the case of degeneration or thinning, the facet joint and the capsule in between bear a heavier than normal load.

Heavy loads can cause advanced wear to the capsule. Eventually, the capsule becomes severely worn or destroyed. Bone on bone contact occurs leading to arthritis of the joint and corresponding discomfort.

Facet joint pain can create another symptom of lower back pain and may further reduce mobility.

Muscle Guarding and Disc Ruptures

The irritation and inflammation in this joint triggers the muscles to spasm and lock to protect the spine from further movement. Locking is known as ‘muscle guarding’.

Although guarding helps to prevent further injury, it is not precise and leads to possible over corrected muscle imbalances that contribute to more injury.

Figure 4.5 illustrates some of the different possible types of injury to the discs in your spine. As we age, it is natural to have wear and tear on the spine, especially to the lumbar region. Ruptures are very common and do reabsorb and repair over time.

Because they require long periods of time to heal from a tear or rupture (weeks to months), they tend to lose height as a result during the repair process. In most cases, the discomfort has already become manageable before this process is complete.

Unfortunately, we will usually return to our daily activities before healing is complete. By returning too soon, it increases the likelihood of an incomplete and poor repair process, thereby accelerating the aging process.

Disc Degeneration

This protective cushion does become thinner as we age and the very limited blood supply that provide nutrients to them also disappear after time. Therefore it would be typical to receive a diagnosis as we age that is termed as “degenerative disc disease” or “DDD”.

As unsettling as it sounds to receive a diagnosis of a disease, it is generally the most common way to describe the aging process. Sometimes, it is described as a ‘disorder’ or a ‘disease’.

DDD diagnosis is sometimes graded as mild, moderate or severe. Almost everyone over the age of 30 is diagnosed with a ‘mild’ form. The L5-S1 (the lowest disc) that sits in between our lumbar column and pelvis is usually to first to exhibit this type of wear. This ‘disease’ or ‘disorder’ is what we need to be concerned about as we should try to delay or prevent this aging process.

What you do on a daily basis will affect the acceleration of this aging process.

For most of us with low back pain, the process has already begun, and our primary concern is to slow it down as much as possible.

There are many treatments offered to help address any premature degeneration. Some range from dietary changes, decompression to physiotherapy and of course exercises. With the right treatment, you can successfully address this problem.

The Low Back Pain Program and eBook help to address the physical limitations, imbalances and needs of our supporting muscle groups in order to have relief and to learn the ways to overcome the discomfort.

We can improve it to provide support and relief so that we may achieve not only pain relief but to use our muscles properly. It gives us more opportunity to perform the daily exercises and tasks that instead of causing harm, will help condition and protect us instead.

References:

- Solving Back Problems – Dr. J. Sutcliffe. Timelife Custom Publishing. Health Fact File. 1999. RD768S82

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

- Herniated/Slipped Disk-http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001478/

- Intervertebral Disk Degeneration and Repair – James Dowdell, MD Mark Erwin, MD Theodoe Choma, MD Alexander Vaccaro, MD, PhD James Iatridis, PhD Samuel K. Cho, MD Neurosurgery (2017) 80 (3S): S46-S54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyw078 Published: 21 February 2017